No other nation in the world says ‘Welcome’ as often as the Egyptians, and every time, they mean it. While the ancient civilization of Egypt continues to amaze, contemporary Egyptians are equally remarkable.

The Great Sphinx

The Enigmatic Great Sphinx: A Monument of Mysteries

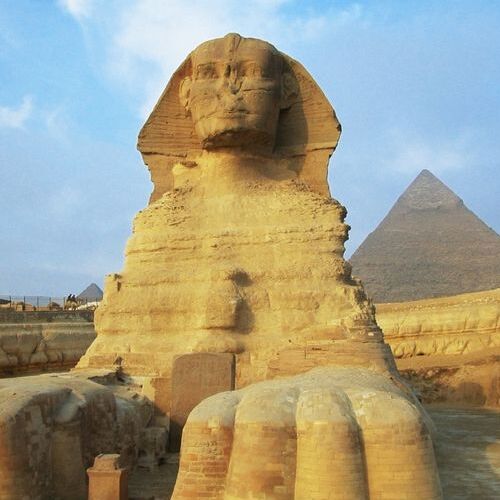

Rising majestically from the timeless sands of the Giza Plateau, adjacent to Khafre’s valley temple, the Great Sphinx stands as a sentinel of Egypt’s rich history. Revered as a national emblem, this colossal statue has ignited the curiosity of generations, captivating the hearts and minds of travelers, scholars, poets, and writers for centuries. Yet, despite centuries of exploration and study, it continues to veil itself in enigmatic mysteries that have intrigued adventurers for millennia.

Carved from an outcrop of limestone, a residue from the quarrying of stones for the Great Pyramid, the Great Sphinx resides in a rectangular trench, framed by Khafre’s causeway to the south, a modern roadway to the north, and the ancient ‘Sphinx Temple’ to the east. In the shadow of this mighty monument lies a reconstructed New Kingdom religious structure, thought to date back to the reign of Amenhotep II, adding a layer of historical complexity to the site.

The Great Sphinx takes on the form of a crouching lion with the visage of a human, traditionally believed to represent Khafre, though this attribution remains a subject of spirited debate. While sphinxes are a common motif in Egyptian statuary, the Great Sphinx’s unique architecture has kindled the imaginations of many, giving rise to theories of an ancient civilization predating the builders of the pyramids. However, despite its enigmatic aura, recent excavations and restorations have uncovered no hidden chambers or traces of vanished civilizations, leaving some to speculate on a conspiracy to keep such secrets veiled from the world.

The colossal body of the Sphinx, stretching nearly 60 meters in length and soaring 20 meters in height, was sculpted from alternating layers of soft and hard marly limestone sediments, formed during the geological Eocene period. These limestone layers were quarried and employed in various Old Kingdom construction projects, with the remnants now aiding in tracking the origins of nearby structures. For instance, the massive blocks forming the walls of Khafre’s valley temple likely hailed from the upper body of the Sphinx itself, and certain limestone blocks of the Sphinx Temple originated from the vicinity of the Sphinx’s chest.

The head of the Sphinx portrays an Egyptian ruler donning a Nemes head-dress, once adorned with a uraeus-serpent on its forehead and a royal beard (fragments of which are now displayed in museums). The human head appears small in proportion to the lionine body, and some speculate that the body may have been elongated to accommodate a natural rock fissure, which would have impeded the completion of the carving of the rear quarters.

The Great Sphinx has weathered the ages, its body buried in the desert sands a mere thousand years after its creation, during the 18th Dynasty. Its reawakening is attributed to a young Prince Tuthmose (later Tuthmose IV), who dreamt of the Sphinx entreating him to free its body from the encroaching sands. Years later, as pharaoh, Tuthmose remembered this vision, leading to the excavation and the placement of a commemorative stela between the Sphinx’s forepaws.

Records suggest that Tuthmose IV initiated the first restoration, and remains of mudbrick walls bearing his name surround the Sphinx. A renewed interest in the Sphinx flourished during the reign of Amenhotep II, under the epithet “Horemakhet” (Horus of the Horizon), marking the beginning of a cult revival. Further restorations are documented, including those by Rameses II and his son, Prince Khaemwaset. The Saite Period also witnessed attention to the Sphinx, as indicated by the ‘Inventory Stela’ east of the Great Pyramid. The Roman era saw the Sphinx become a beloved tourist attraction, prompting efforts at clearing and preservation by Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Septimus Severus.

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte arrived in Egypt, his awe for the Sphinx inspiring the excavation of the buried monument by his scientific team. The unveiling of the Dream Stela marked a pivotal moment. Subsequent explorations by Giovanni Battista Caviglia in 1816 yielded fragments of the Sphinx’s false royal beard, now housed in the British Museum.

More comprehensive excavations in the 1920s, led by French archaeologist Emile Baraize, brought to light the temple concealed beneath the Sphinx’s forepaws, and restored various elements, including a crack on the statue’s head. Conservation efforts continued sporadically, with noteworthy work by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization between 1955 and 1989. The most recent phase of conservation, under the guidance of Zahi Hawass and foreign experts, addressed issues of deterioration stemming from humidity, rising water tables, and air pollution. Restoration efforts focused on the south forepaw, southern flank, and the tail, breathing new life into this ancient enigma.

The Great Sphinx’s colossal figure gazes eastward, its monumental presence linked to solar worship. Identified with the gods Re and Horus, it embodies the eternal cycle of the sun rising and setting on the horizon. Is it a living representation of Khafre or a mythical guardian of the necropolis, offering homage to the sun-god?

As the sun sets and rises over the Giza Plateau, the Great Sphinx endures, its enigmatic smile hiding secrets of the ages, waiting for those intrepid enough to unravel the mysteries shrouded in its silent embrace.

Created On April 07, 2020

Updated On July 22 , 2025

Giza Travel Guide