Exploring the Great Sphinx of Giza Overtime

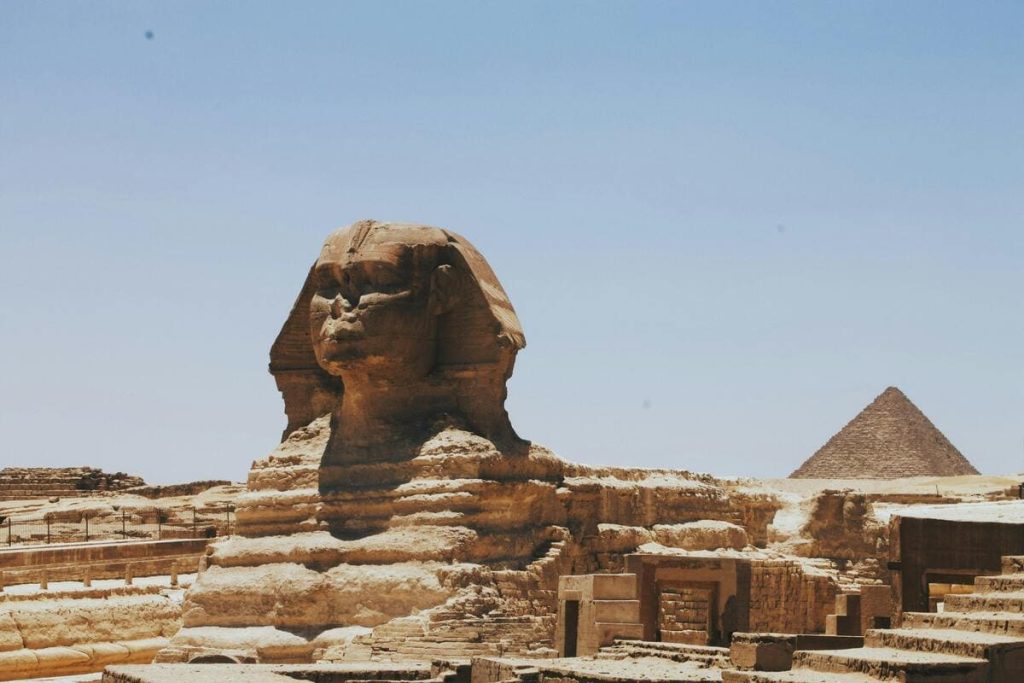

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a magnificent limestone statue depicting a reclining sphinx, which combines the body of a lion with a human head. Positioned to face from west to east, it majestically rests on the Giza Plateau near the Nile’s west bank in Egypt. Historians believe the Sphinx’s visage likely represents Pharaoh Khafre. Originally carved from the natural bedrock, the statue has been subsequently restored with additional limestone blocks. It spans an impressive length of 73 meters from paw to tail, stands 20 meters tall from its base to the top of the head, and measures 19 meters wide across the back haunches.

As the oldest monumental sculpture recognized in Egypt, the Sphinx also ranks among the world’s most iconic statues. Archaeological studies indicate that it was crafted by the ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom under Pharaoh Khafre’s rule, around 2558 to 2532 BC.

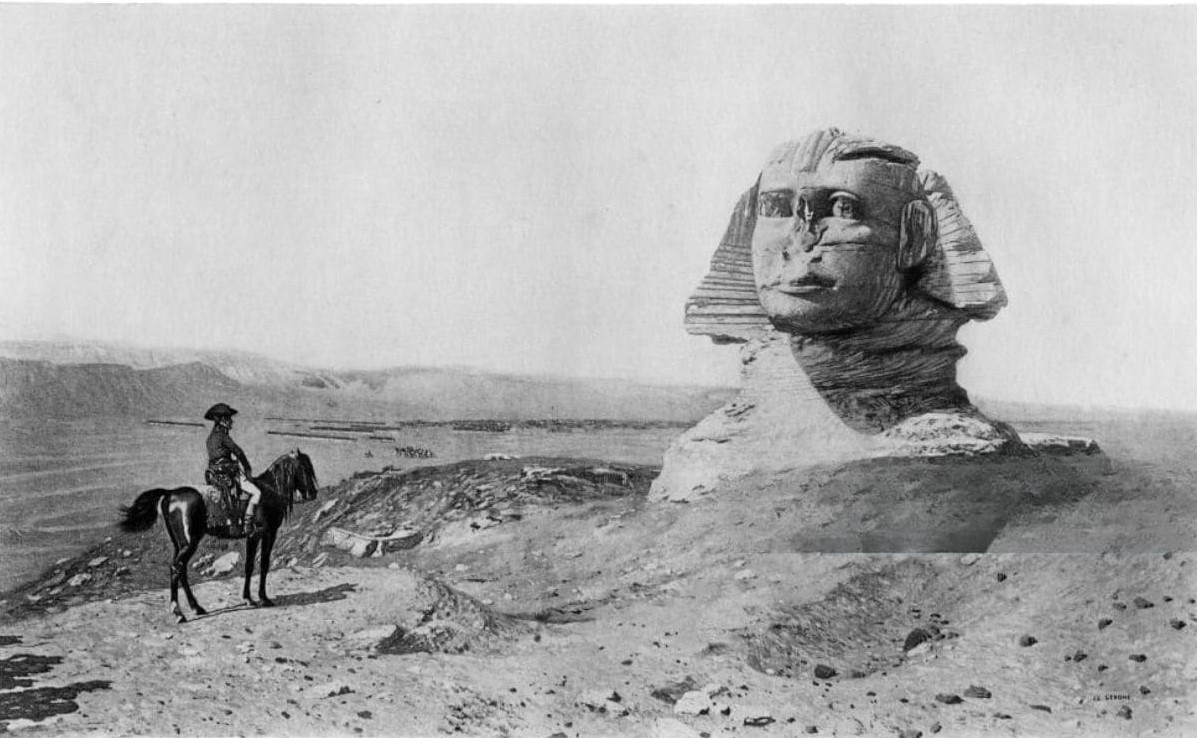

There is some mystery surrounding the damage to the Sphinx’s nose, with evidence hinting at a purposeful removal using tools such as rods or chisels. This debunks the long-held myth that Napoleon’s troops blasted it off with cannon fire during their 1798 campaign in Egypt. Indeed, historical depictions and descriptions, including those by the 15th-century historian al-Maqrīzī, confirm that the nose was missing well before Napoleon’s arrival.

The original name given to the Sphinx by its creators during the Old Kingdom remains unknown, primarily because the construction of the Sphinx temple, its enclosure, and perhaps even the Sphinx itself, was incomplete at the time, leaving behind scant cultural materials. However, by the New Kingdom era, the Sphinx was venerated as the solar deity Hor-em-akhet, meaning “Horus of the Horizon” and often Hellenized as Harmachis. This deity association is highlighted in the Dream Stele by Pharaoh Thutmose IV, dating from around 1401–1391 or 1397–1388 BC.

The Sphinx: Name and Legends

The name “Sphinx,” which became common in classical antiquity, refers to a Greek mythological beast typically depicted with a woman’s head and a lion’s body, sometimes featuring wings of an eagle. This was about 2,000 years after the Sphinx’s estimated construction. Notably, unlike its Greek counterparts, the Great Sphinx features a man’s head and lacks wings. The English word “sphinx” derives from the ancient Greek “Σφίγξ,” linked to the verb “σφίγγω,” meaning “to squeeze,” referring to the mythical Greek sphinx known for strangling those unable to answer her riddle.

In the medieval period, Arab historians like al-Maqrīzī referred to the Sphinx by various Arabized names derived from the Coptic, such as Belhib, Balhubah, and Belhawiyya. These names trace back to the Ancient Egyptian “Pehor” or “Pehoron,” associated with the Canaanite god Hauron. The modern Egyptian Arabic name for the Sphinx, أبو الهول (ʼabu alhōl or ʼabu alhawl, meaning “The Terrifying One” or “Father of Dread”), reflects a phono-semantic matching of these older names.

The Construction and Origins of the Great Sphinx

During the Old Kingdom, around 2500 BC, the Great Sphinx of Giza is believed to have been constructed under the auspices of Pharaoh Khafre, who also commissioned the Second Pyramid at Giza. The Sphinx was meticulously carved from a single monolith of bedrock that also served as a quarry for the nearby pyramids and other structures.

Egyptian geologist Farouk El-Baz proposed that the Sphinx’s head may have been sculpted first from a natural yardang—a ridge of bedrock shaped by the wind that sometimes resembles animal forms. He suggests that the surrounding “moat” or “ditch” was excavated later, enabling the full body of the Sphinx to be shaped. The stones extracted from this process were then utilized to build a temple situated directly in front of the Sphinx. However, neither this temple nor the enclosure around the Sphinx were completed, and the lack of Old Kingdom cultural artifacts related to a Sphinx cult indicates that such a cult likely did not exist at that time.

Selim Hassan, who conducted excavations around the Sphinx in 1949, expressed caution in attributing the creation of the Sphinx to Khafre due to the absence of contemporary inscriptions linking the Sphinx directly to him. He noted that while the evidence strongly suggests Khafre’s involvement, it remains circumstantial until definitive proof can be uncovered.

The construction logistics also indicate that the Khafre funerary complex, including his Valley Temple and the causeway connecting it to his pyramid, was established prior to the planning of the Sphinx. This is evident from the dismantling of the northern perimeter-wall of the Valley Temple to build the Sphinx temple and the positioning of the south wall of the Sphinx enclosure, which aligns with the pre-existing causeway. The lower base level of the Sphinx temple further supports the notion that it was built after the Valley Temple, integrating these structures into a comprehensive funerary complex dedicated to Khafre.

Revival and Reverence: The Sphinx Through the Ages

In the New Kingdom, the Great Sphinx of Giza gained renewed attention and religious significance. After the Giza Necropolis had been abandoned during the First Intermediate Period and the Sphinx buried up to its shoulders in sand, a significant archaeological effort was made by Thutmose IV around 1400 BC. Thutmose IV managed to excavate the front paws of the Sphinx and installed the Dream Stele between them. This granite slab, possibly repurposed from one of Khafre’s temples, bore inscriptions that were partly damaged by the time of its discovery. The text suggested a divine conversation where the Sphinx, personified as the sun god Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum, proclaimed Thutmose IV as his chosen ruler and requested protection from the encroaching sands.

The Dream Stele text is an important artifact linking the Sphinx to Pharaoh Khafre, though parts of its text are incomplete. Notably, the stele’s inscriptions include appeals for offerings and praises to maintain the statue, indicating its continued worship under the name Atum-Hor-em-Akhet, another form of the sun god.

In the subsequent centuries, the cult surrounding the Sphinx continued to evolve. By the time of Amenhotep II (1427–1401 or 1397 BC), nearly a millennium after its original construction, a temple was erected to the northeast of the Sphinx dedicated to Hor-em-akhet, the “Horus of the Horizon.”

The Sphinx’s status as a monument of interest persisted into the Graeco-Roman period, when it became a popular site for tourism and political expression. Roman emperors and officials, including Nero and the governor Tiberius Claudius Balbilus in the first century AD, sponsored further clearing of sand and the construction of infrastructure around the Sphinx to facilitate access and viewing. A wide stairway leading to a viewing platform was built in front of the Sphinx’s paws, highlighting its importance as an antiquity worth preserving and showcasing.

Throughout these periods, the Sphinx not only served as a religious and cultural symbol but also as a beacon attracting both ancient pilgrims and tourists, reflecting its enduring legacy as one of Egypt’s most revered and enigmatic monuments.

Pliny's Perspective and Roman Restorations of the Sphinx

Pliny the Elder, an ancient Roman author, provides a fascinating account of the Great Sphinx of Giza, highlighting both its physical and cultural significance. He noted that in his time, the Sphinx was seen not just as an impressive work of art, but also as a divine entity by the local population. They believed it to be the burial place of King Harmaïs, a figure likely confused with one of the pharaohs associated with the Sphinx, and thought that it had been transported from afar. Contrary to these local legends, Pliny correctly identified that the Sphinx was carved from the solid bedrock of the Giza plateau.

Pliny also described the Sphinx’s face as being painted red, a detail that underscores the ceremonial and religious importance of the statue. He provided detailed measurements: the head’s circumference around the forehead was 102 feet, the length of its feet was 143 feet, and the height from the belly to the top of the asp (a symbol often worn on the headgear of pharaohs) on its head was 62 feet.

Additionally, a stela dated to 166 AD records the restoration of the retaining walls around the Sphinx, indicating ongoing maintenance and restoration efforts during the Roman period. The last Roman Emperor to be associated with the monument was Septimius Severus around 200 AD. Following the decline of Roman influence in the region, the Sphinx once again succumbed to the sands of the desert, obscuring its grandeur until future rediscoveries and excavations.

Medieval and Early Modern Interpretations of the Sphinx

During the Middle Ages, interpretations and beliefs surrounding the Sphinx continued to evolve beyond ancient Egyptian religious practices. Non-Egyptians, including the Sabians of Harran, viewed the Sphinx as a sacred monument, believing it to be the burial place of Hermes Trismegistus, a figure revered in several mystical and philosophical traditions. Arab authors from the period described the Sphinx as a protective talisman, guarding the surrounding area from desert encroachments. Notably, al-Maqrizi referred to it as the “talisman of the Nile,” suggesting that locals believed the annual flooding cycle of the Nile depended on the statue.

In the early modern period, European travelers and scholars brought their perspectives, often influenced by a blend of romanticism and mystique. From the 16th to the 19th century, many European descriptions portrayed the Sphinx with feminine features—depicting it as having the face, neck, and breast of a woman. These accounts, while varying in detail, contributed to the evolving mythos surrounding the Sphinx in Western thought. Notably, John Lawson Stoddard’s description from the 19th century captures the awe and reverence felt by many visitors, emphasizing the Sphinx’s antiquity and enigmatic presence amidst the sands.

Artistic representations of the Sphinx during this period also varied significantly, influenced by the illustrators’ and engravers’ imaginations rather than accurate archaeological findings. These images often bore little resemblance to the actual Sphinx, showcasing a wide array of interpretations about its appearance and symbolism.

Modern Excavations: Unveiling the Great Sphinx

The history of modern excavations at the Great Sphinx of Giza reveals significant efforts and discoveries that have contributed to our understanding of this ancient monument. In 1817, Giovanni Battista Caviglia, an Italian explorer and archaeologist, led a groundbreaking archaeological dig that successfully uncovered the Sphinx’s chest completely, marking a pivotal moment in the modern study of the Sphinx.

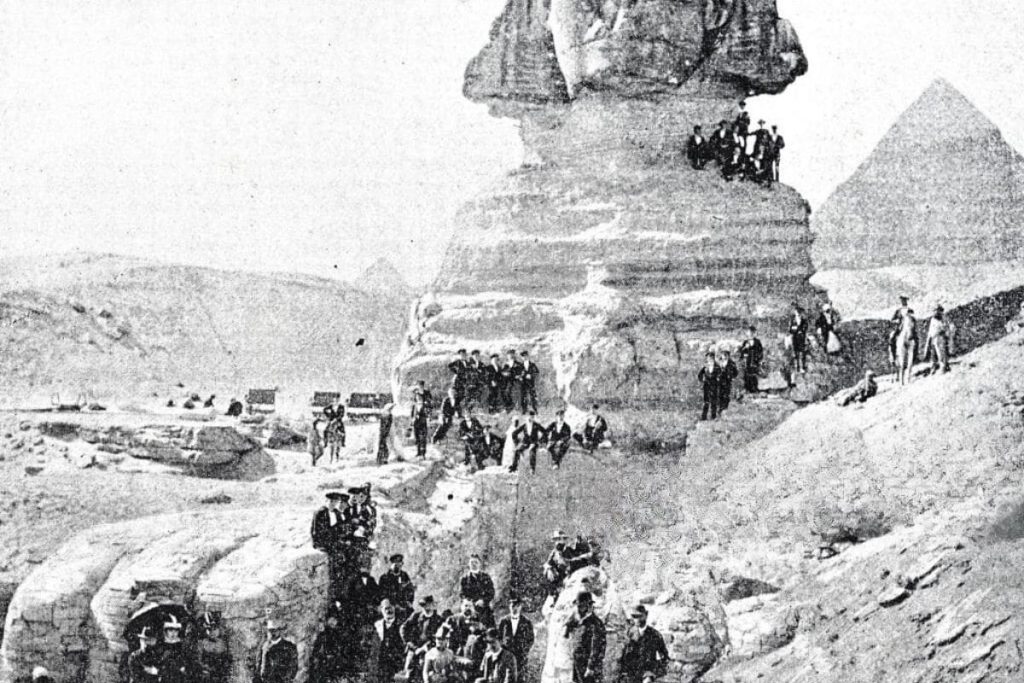

The work continued into the late 19th century, with substantial progress made in 1887 when the chest, paws, altar, and surrounding plateau were fully exposed. During this excavation, flights of steps were also unearthed, allowing for accurate measurements of the Sphinx. The findings included that the height from the lowest of the steps to the top of the Sphinx was one hundred feet, and the area between the paws, which once housed an altar, measured thirty-five feet in length and ten feet in width. Notably, a stele belonging to Thutmose IV was discovered during these efforts. This stele recorded a dream in which Thutmose IV was commanded to clear away the sands accumulating around the Sphinx, highlighting the historical significance and continual maintenance efforts directed at the Sphinx over the centuries.

Eugène Grébaut, serving as the French Director of the Antiquities Service, was also instrumental in these excavation efforts, playing a key role in the ongoing work to clear the sands from around the Sphinx. His contributions, alongside those of other archaeologists, have been crucial in preserving and revealing more details about the Great Sphinx, ensuring its legacy as a symbol of ancient Egyptian engineering and religious devotion.

Debates and Theories on the Age of the Sphinx

The age of the Great Sphinx and its surrounding temples has long been a subject of debate among Egyptologists, revealing a range of theories based on archaeological evidence and interpretations.

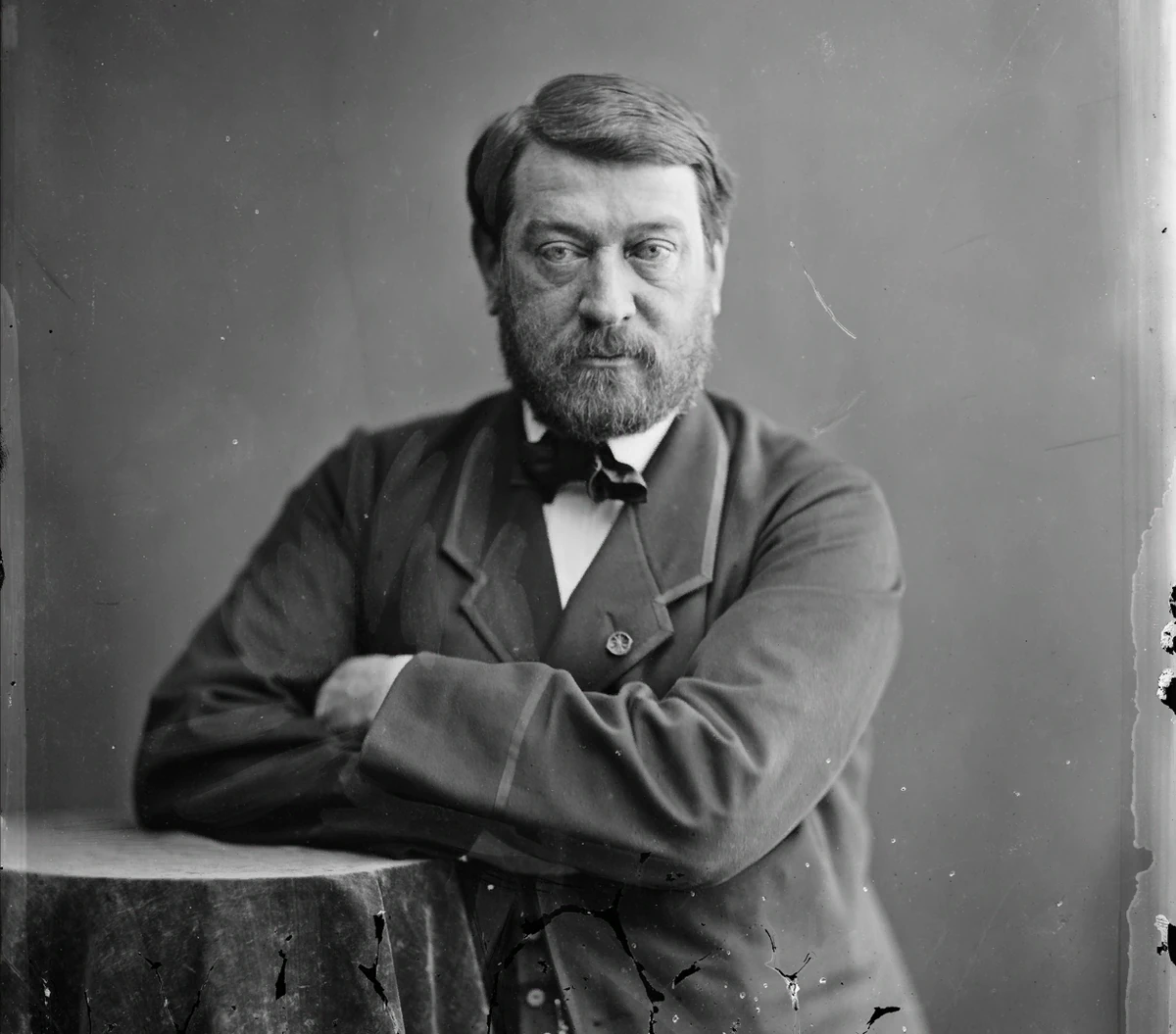

Auguste Mariette and the Inventory Stela

In 1857, Auguste Mariette, founder of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, discovered the Inventory Stela, which dates from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (circa 664–525 BC). The stela suggests that Khufu encountered the Sphinx already buried in sand, implying that it predated him. However, this claim is viewed skeptically by scholars as likely being a piece of historical revisionism, fabricated by local priests to attach an ancient legacy to the contemporary temple of Isis for political and economic gains.

Flinders Petrie's Observations

In 1883, Flinders Petrie commented on the dating of the Khafre Valley Temple, and by extension, the Sphinx, suggesting that recent discoveries indicated it was not constructed before Khafre’s reign in the Fourth Dynasty.

Gaston Maspero's Conclusion

Gaston Maspero, after a 1886 survey, concluded that the Sphinx must predate Khafre and his predecessors based on the Dream Stele, which mentions Khafre’s cartouche, placing the Sphinx’s creation possibly as far back as the Fourth Dynasty (circa 575–2467 BC). Maspero believed the Sphinx to be the most ancient monument in Egypt.

Ludwig Borchardt’s Theory

Ludwig Borchardt attributed the Sphinx to the Middle Kingdom, arguing that its facial features were characteristic of the 12th Dynasty and particularly resembled Amenemhat III.

E. A. Wallis Budge’s Views

In his 1904 work, The Gods of the Egyptians, E. A. Wallis Budge posited that the Sphinx existed during the time of Khafre but was likely much older, dating back to the end of the archaic period around 2686 BC.

Selim Hassan’s Reasoning

Selim Hassan believed the Sphinx was constructed after the completion of the Khafre pyramid complex, suggesting it is not as old as some other theories propose. These differing opinions highlight the complexities and challenges of definitively dating ancient monuments like the Sphinx, with each theory grounded in varying interpretations of archaeological and textual evidence.

Modern Research and Alternative Theories on the Sphinx

Modern research and alternative hypotheses continue to challenge traditional views about the age and origin of the Great Sphinx of Giza, leading to new interpretations and debates among scholars.

Rainer Stadelmann's Hypothesis

Rainer Stadelmann, a former director of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo, analyzed the nemes (headdress) and the now-detached beard of the Sphinx. He concluded that their style is more indicative of the Pharaoh Khufu (2589–2566 BC), rather than Khafre. Stadelmann supported his theory by suggesting that Khafre’s Causeway was constructed to align with a pre-existing structure, which he argues could only have been the Sphinx, given its location.

Vassil Dobrev's Theory

In 2004, Vassil Dobrev of the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale in Cairo proposed that the Great Sphinx might have been built by Djedefre (2528–2520 BC), Khafre’s half-brother and a son of Khufu. Dobrev suggested that Djedefre created the Sphinx in the likeness of his father, Khufu, to associate him with the sun god Ra and restore respect for their dynasty. This theory is bolstered by the observation that the causeway connecting Khafre’s pyramid to the temples was built around the Sphinx, implying its pre-existence. However, this hypothesis remains contentious, with Egyptologists like Nigel Strudwick requesting further evidence and expressing skepticism about related claims, such as Djedefre’s pyramid being a sun temple.

Colin Reader's Geological Perspective

Colin Reader, a geologist, focused on the erosion patterns within the Sphinx enclosure, which he attributes to water runoff from the Giza plateau. He argued that the significant hydrological changes caused by quarrying suggest the Sphinx predates the nearby quarries—and by extension, the pyramids. Reader points to the use of large cyclopean stones in part of the Sphinx Temple and the alignment of the causeway with the pyramids as evidence that these structures were planned around a pre-existing monument like the Sphinx. He proposes that the Sphinx could date back to the late Predynastic or Early Dynastic periods, slightly older than traditionally thought, based on the advanced masonry skills evident at that time.

Recent Restorations

Restorations have been ongoing to preserve the Sphinx against natural erosion and damage. Notably, in 1931, engineers repaired the Sphinx’s head after part of its headdress fell off in 1926. A concrete collar was added between the headdress and the neck, which has altered its profile somewhat controversially. Further extensive renovations were carried out in the 1980s and again in the 1990s, focusing on both the stone base and the raw rock body of the Sphinx. These diverse perspectives demonstrate the complexities and evolving understanding of the Great Sphinx, highlighting both its historical importance and the challenges of preserving such an iconic ancient monument.

The Mystery of the Missing Nose and Other Sphinx Secrets

The Great Sphinx of Giza, an iconic symbol of ancient Egypt, has long been a subject of mystery and intrigue, particularly regarding the missing nose. Detailed examinations suggest that the nose was intentionally removed using tools like rods or chisels, which were inserted into the nose area and then levered to pry it off. The mystery of the missing nose has spawned numerous folk tales, including the widely circulated but incorrect claim that it was destroyed by Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. However, this myth is debunked by sketches made by Frederic Louis Norden in 1737, which show the nose already missing, a full 60 years before Napoleon’s campaign.

Historical accounts attribute the damage to various causes over the centuries. Some 10th-century Arab authors considered the damage a result of iconoclastic attacks. More specifically, the Arab historian al-Maqrīzī, writing in the early 15th century, attributed the act to Muhammad Sa’im al-Dahr, a Sufi Muslim in 1378 who was reportedly dismayed by local peasants worshipping the Sphinx for better harvests. Al-Maqrīzī noted that the defacement led to increased sand cover over the Giza Plateau, which locals viewed as divine retribution. Furthermore, Al-Minufi in the 15th century linked the damage to divine punishment for the defacement during the Alexandrian Crusade in 1365.

In addition to the nose, the Sphinx originally featured a ceremonial pharaonic beard, fragments of which are now housed in the British Museum. There is debate among Egyptologists about whether this beard was part of the original Sphinx or added later. Vassil Dobrev has posited that if the beard were original, its detachment would likely have caused noticeable damage to the Sphinx’s chin

The coloration of the Sphinx also points to its vibrant past, with residues of red pigment on its face and traces of yellow and blue elsewhere on the statue. Egyptologist Mark Lehner has suggested that these colors indicate that the Sphinx was once vividly painted, giving it a far more striking appearance in ancient times than the monochrome tones we see today.

Hidden Tunnels and Structural Features of the Sphinx

The Great Sphinx of Giza, with its layers of history and mystery, is not just notable for its missing nose and vivid coloration in ancient times but also for its intriguing structural features, including several holes and tunnels that have sparked curiosity and speculation over the centuries.

Hole in the Sphinx's Head

During his travels in 1565–1566, Johann Helffrich recorded a fascinating observation about the Sphinx. He described a priest entering a hole at the top of the Sphinx’s head and speaking in such a way that it seemed as if the Sphinx itself was the source of the voice. This anecdote has contributed to the mystical aura surrounding the Sphinx. Additionally, various stelae from the New Kingdom depict the Sphinx wearing a crown, suggesting that the hole might have originally served as an anchoring point for such a crown. In 1926, Émile Baraize sealed this hole with a metal hatch, adding a modern layer to the ancient structure.

Perring’s Hole

Another notable feature is known as Perring’s Hole, located just behind the Sphinx’s neck. In 1837, under the direction of Howard Vyse, John Shae Perring attempted to drill a tunnel in this location. Unfortunately, the drilling rods became stuck at a depth of 27 feet, and attempts to free them with explosives caused additional damage. It wasn’t until 1978 that the hole was cleared, revealing among the debris a fragment of the Sphinx’s nemes headdress, further indicating the historical complexity of the monument.

Major Fissure

A significant natural fissure cuts through the waist of the Sphinx, first explored by Auguste Mariette in 1853. This fissure is particularly wide at the top of the Sphinx’s back, measuring up to 2 meters (6.6 feet). Baraize took measures to stabilize this fissure in 1926 by sealing the sides and installing a roofing made of iron bars, limestone, and cement. He also placed an iron trap door at the top. The sides of this fissure might have been artificially squared off, while the bottom remains an irregular bedrock, slightly elevated from the surrounding floor. A narrower crack continues deeper, hinting at the geological challenges the Sphinx has faced through millennia.

These structural interventions highlight both the vulnerabilities of the Sphinx due to natural and human-induced damage and the ongoing efforts to preserve and study this iconic monument.

New Insights into the Sphinx's Hidden Features

In 1926, significant progress was made in uncovering parts of the Sphinx under the direction of Émile Baraize, which led to the discovery of an opening to a tunnel at the north side of the Sphinx’s rump, at floor-level. This tunnel was initially closed off with a masonry veneer and gradually faded from common memory.

Rump Passage

Over fifty years later, in the 1980s, the existence of this so-called “rump passage” was recalled by three elderly men who had worked as basket carriers during the 1926 clearing. Their recollections prompted the rediscovery and subsequent excavation of the passage.

Structure of the Rump Passage

Over fifty years later, in the 1980s, the existence of this so-called “rump passage” was recalled by three elderly men who had worked as basket carriers during the 1926 clearing. Their recollections prompted the rediscovery and subsequent excavation of the passage. The rump passage is divided into an upper and a lower section, joined at roughly a 90-degree angle:

Upper Section

The upper part ascends 4 meters (about 13 feet) above the ground-floor, heading in a northwest direction.

It runs between the masonry veneer and the core body of the Sphinx, ending in a niche that is 1 meter (about 3.3 feet) wide and 1.8 meters (about 5.9 feet) high.

The ceiling of this niche is composed of modern cement, which likely seeped down from the filling of the gap between the masonry and core bedrock located approximately 3 meters (about 9.8 feet) above.

Lower Section

This part of the passage descends steeply into the bedrock toward the northeast for a distance of roughly 4 meters (about 13 feet) and reaches a depth of 5 meters (about 16 feet).

It ends in a cul-de-sac pit at the groundwater level. The entrance measures 1.3 meters (about 4.3 feet) wide, narrowing to about 1.07 meters (about 3.5 feet) toward the end.

Among the debris found here were pieces of tin foil, the base of a modern ceramic water jar, more tin foil, modern cement, and a pair of shoes, suggesting recent human activity or interference.

The construction of the passage is believed to have been top-down, starting high on the rump, with the current access at floor level potentially created later. Howard Vyse’s diary entries from February 27 and 28, 1837, mention “boring” near the tail of the Sphinx, which points to him possibly being the original creator of this passage. However, there is another interpretation that this shaft could be of ancient origin, perhaps serving as an exploratory tunnel or an unfinished tomb shaft.

This passage adds another layer to the Sphinx’s rich and complex history, suggesting various phases of construction, use, and exploration throughout its existence.

Explorations and Structural Discoveries at the Sphinx

Niche in Northern Flank

A niche in the northern flank of the Sphinx was documented in a photograph from 1925 showing a man standing below floor level within the Sphinx’s core body. This niche was sealed off during the restoration efforts in 1925-1926, illustrating the ongoing modifications and conservation efforts aimed at stabilizing and preserving the Sphinx.

Gap Under Southern Large Masonry Box

Speculation also exists about another possible opening at floor level within a large masonry box on the south side of the Sphinx. Details about this gap remain limited, underscoring the mystery and ongoing discovery process associated with the Sphinx’s structure.

Space Behind Dream Stele

The space located behind the Dream Stele, situated between the paws of the Sphinx, has been covered and protected by an iron beam and cement roof, equipped with an iron trap door. This construction reflects efforts to preserve the integrity of the structure and protect it from environmental factors.

Keyhole Shaft

In 1978, an excavation led by Hawass revealed a square shaft at the ledge of the Sphinx enclosure, located opposite the northern hind paw. This shaft, which measures 1.42 by 1.06 meters and about 2 meters deep, was interpreted by archaeologist Mark Lehner as an unfinished tomb and was aptly named the “Keyhole Shaft” due to the shape of the cuttings in the ledge above it resembling a traditional (Victorian era) keyhole turned upside down.

Pseudohistory and Speculative Theories

Various pseudohistorical theories have been proposed over the years concerning the Sphinx’s origins and purpose, often lacking in sufficient evidence or contradicted by established archaeological, geological, and historical data.

Ancient Astronauts and Atlantis Theories

Some fringe theories, like the Orion correlation theory, suggest that the Sphinx was aligned to face the constellation of Leo during the vernal equinox around 10,500 BC, tying it to the pseudoarchaeological idea of ancient astronauts or connections to Atlantis. Such theories are widely rejected by mainstream scholars who argue that no substantial evidence supports these claims, and the Sphinx’s eastward orientation aligns with known ancient Egyptian solar cult practices.

Sphinx Water Erosion Hypothesis

The Sphinx water erosion hypothesis argues that the type of weathering observed on the Sphinx’s enclosure walls could only be caused by extensive rainfall, suggesting a much older date than traditionally accepted. This hypothesis, promoted by figures like René Schwaller de Lubicz, John Anthony West, and geologist Robert M. Schoch, is considered pseudoarchaeology by the academic community, which cites archaeological and climatological evidence to the contrary.

Hall of Records

Predictions by figures like Edgar Cayce in the 1930s about a “Hall of Records” beneath the Sphinx, purportedly holding knowledge from Atlantis, fueled much speculative interest, especially in the 1990s. However, this speculation lost momentum when no such hall was discovered as predicted.

Alternative Iconographic Origins

Author Robert K. G. Temple proposed that the Sphinx was originally a statue of Anubis, the jackal god of funerals, and that its face was later recarved to resemble a Middle Kingdom pharaoh, specifically Amenemhet II. Temple’s theory is based on stylistic analysis of the eye make-up and headdress pleats but remains speculative without substantial archaeological backing.

These diverse theories and discoveries illustrate the complex and multifaceted nature of scholarly and public engagement with the Sphinx, reflecting a blend of evidence-based archaeology and the allure of mystery that surrounds one of the world’s most iconic ancient monuments.

The space located behind the Dream Stele, situated between the paws of the Sphinx, has been covered and protected by an iron beam and cement roof, equipped with an iron trap door. This construction reflects efforts to preserve the integrity of the structure and protect it from environmental factors.