Introduction

Islamic Architectural Heritage in Egypt offers an extraordinary journey through over a thousand years of artistry, spirituality, and design—from early Arab fortresses to the intricate domes of Mamluk mosques and the slender elegance of Ottoman minarets. At its heart lies Cairo’s historic Islamic quarter, famously dubbed the “City of a Thousand Minarets,” with Al-Azhar Mosque as a central landmark. Yet the legacy extends far beyond Cairo, from Alexandria’s Mediterranean coast to the treasures of Luxor in Upper Egypt. This guide explores the historical context, defining architectural styles, and essential sites to visit across Islamic Cairo and other key cities.

Historical Context of Islamic Architecture in Egypt

Early Islamic & Fatimid Era (7th–12th centuries): Islam arrived in 641 AD with the conquest of Egypt. The first mosque in Africa, Amr ibn al-As, was established in the new garrison town of Fustat (Old Cairo). In 969 AD the Fatimid Dynasty founded Al-Qahira (Cairo) as their capital. The Fatimids built city walls and gates (Bab al-Nasr, Bab al-Futuh, Bab Zuweila) and monumental mosques such as Al-Azhar Mosque (970–972) ([Al-Azhar Mosque Under the Fatimids, Cairo prospered as a cultural center, rivaling Baghdad ([The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of Fatimid architecture drew on Tulunid techniques but developed its own refined style – their first congregational mosque, Al-Azhar, and later Al-Hakim and Al-Aqmar mosques, introduced decorative motifs and innovative use of stone ([The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum

Ayyubid & Mamluk Era (12th–16th centuries): After 1171, Salah ad-Din (Saladin) ended Fatimid rule and introduced Sunni Ayyubid rule. Saladin fortified Cairo by building the Citadel of Cairo (1176–1183) on the Muqattam Hills as a defensive stronghold and seat of government Cairo Citadel – Discover Egypt’s Monuments – Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities In 1250 the Mamluks seized power, ushering in a golden age of art and architecture. The Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517) endowed Cairo with an astonishing array of mosques, madrasas, khanqahs (Sufi lodges), and caravanserais. They expanded the city beyond the old Fatimid walls and filled the skyline with domes and minarets. Mamluk architecture became highly distinguished – sultans like Qalawun, Hassan, Barquq, and Al-Ghuri built huge complexes featuring intricate stone carvings, pointed arches, towering façades, and stalactite (muqarnas) cornices. Many of these 14th–15th century structures still dominate Historic Cairo. For example, the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hassan (1356–1363) is considered one of the masterpieces of Mamluk architecture and the most stylistically unified monument in Cairo ([File:Flickr – HuTect ShOts – Masjid of Sultan Hassan مسجد ومدرسة السلطان حسن – Cairo – Egypt –

Ottoman & Modern Era (16th–20th centuries): After 1517, Egypt became part of the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman governors generally maintained the existing Mamluk cityscape but added their own touches. Limited space in medieval Cairo meant many Ottoman works were renovations of earlier buildings. A distinctive Ottoman contribution is the use of Iznik-style tilework and the introduction of the Turkish mosque plan. The most prominent example is the **Mosque of Muhammad Ali** (completed 1848) inside the Citadel, with its large central dome and twin minarets, modeled on Istanbul’s grand mosques. In the 19th century, Khedive Ismail’s era saw new European-influenced districts in Cairo, while the old city’s Islamic heritage remained largely intact. Notably, a revival *“neo-Mamluk”* style emerged in the late 19th–early 20th century – for example, Cairo’s **Al-Rifa’i Mosque** (completed 1912) was built to complement Sultan Hassan’s Madrasa across the square, echoing Mamluk designs. Modern Islamic architecture in Egypt continues to draw on this rich heritage, as seen in contemporary mosques that blend traditional forms with modern construction.

Architectural Styles and Influences

Fatimid Style (10th–12th c.): Characterized by a fusion of influences from North Africa and the Levant, Fatimid architecture often employed brick walls with carved stucco and wooden tie-beams, following Tulunid construction methods ([The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of Fatimid mosques like Al-Azhar and Al-Hakim feature hypostyle layouts (columns supporting arcades), with relatively plain exteriors but ornate mihrabs and kufic calligraphy bands. Notably, the Fatimids introduced monumental gateways and richly decorated façades: the Al-Aqmar Mosque (1125) has a famed street-facing stone facade with intricate geometric carving – an innovation at the time ([The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of Fatimid decorative arts (ceramics, wood carving, etc.) also flourished in Cairo, adding to the embellishment of buildings ([The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171) – The Metropolitan Museum of Overall, the Fatimid style is marked by elegant restraint on the exterior and finely crafted details within, reflecting the dynasty’s fusion of North African heritage with Abbasid-era aesthetics

Islamic Insights: The Grand Islamic Cairo Day Tour

Mamluk Style (13th–16th c.): Cairo’s Mamluk architecture is opulent and structurally ambitious, representing the pinnacle of medieval Islamic design in Egypt. Hallmarks of Mamluk style include soaring stone domes (often carved in geometric relief), tiered minarets with elaborate balconies, pointed arches, marble paneling, and muqarnas (stalactite) cornices. Buildings were often large multi-purpose complexes (combining mosque, madrasa, mausoleum, and hospital). The Mamluk love of decoration is evident in elements like finely carved stone arabesque patterns, inlaid marble floors, and bronze doors. They favored bold geometry and calligraphic friezes that wrap façades and courtyards. Persian and Syrian influences can be seen in some forms (e.g. the use of keel arches and star-pattern cresting), but Mamluk creations are unique in their density of ornament and verticality. The result is a skyline of majestic domes and pencil-like minarets. Examples: The Sultan Hassan Mosque is lauded for its harmonious proportions and massive scale – its 76 m long façade and monumental portal are especially impressive ([File:Flickr – HuTect ShOts – Masjid of Sultan Hassan مسجد ومدرسة السلطان حسن – Cairo – Egypt – 16 04 2010 Inside, large iwans face a central courtyard, and coursing Quranic inscriptions adorn the walls. Another example, the Qalawun Complex (1280s), includes a hospital and madrasa with a beautifully carved stone dome and polychrome marble entrance. In sum, the Mamluk style presents a “symphony in stone” – as seen in the intricate carvings and calligraphy of these structures ([A Comprehensive Guide to Visiting the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, Egypt A Comprehensive Guide to Visiting the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, Egypt emphasizing grandeur, craftsmanship, and the pious patronage of sultans.

Ottoman Style (16th–19th c.): Ottoman-era architecture in Egypt blended Turkish forms with local Egyptian elements. Early Ottoman mosques in Cairo were relatively small, often converting existing buildings or infilling city gaps. However, in the 19th century, Ottoman ruler Muhammad Ali modernized the Citadel with a grand royal mosque. The Muhammad Ali (Alabaster) Mosque (built 1828–1848) exemplifies Ottoman style: it features a central dome flanked by semi-domes, pencil-thin Ottoman minarets, and an ornate interior with Turkish tile motifs. Distinctive to Ottoman design is the extensive use of glazed ceramic tile paneling with floral motifs – an art form imported from Istanbul. Domes were often painted or tiled in vibrant colors. Another Ottoman touch is the incorporation of Baroque or Rococo influences in later periods (e.g. carved decoration on mid-19th century sabils and palaces). Yet in Cairo, Ottoman builders also respected local traditions: for example, the Sulayman Pasha Mosque (1528) in the Citadel is a smaller domed mosque that introduced Ottoman prayer-niche styles but kept a modest footprint. In general, Ottoman architecture in Egypt is less prevalent than Mamluk, but its legacy is visible in the skyline through features like the pointed domes and slender minarets of Muhammad Ali’s mosque, which now dominate Cairo’s horizon.

Spiritual Heart of Cairo: Islamic Cairo Private Day Tour

Modern and Revival Styles (19th–20th c.): As Egypt modernized, architects often hearkened back to historic Islamic motifs. The Neo-Mamluk style became popular in the late 1800s for public buildings and continued into the 20th century. One iconic example is the Al-Rifa’i Mosque in Cairo (completed 1912), which was designed as a royal mausoleum with deliberate imitation of Mamluk features – e.g. soaring minarets, a carved dome, and gothic-scale pointed arches – to complement the adjacent Sultan Hassan Mosque. European architects like Max Herz and Mario Rossi contributed to this revival: Rossi, for instance, redesigned Alexandria’s Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi Mosque in the 1920s–40s in an Andalusian-Mamluk hybrid style, complete with four domes and a 73 m minaret ([Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi Mosque -)). During the colonial period, some buildings adopted Moorish Revival or Ottoman Revival facades (the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo, 1903, has a Mamluk-inspired façade). By the late 20th century, Egypt’s new mosques often combined modern materials with traditional layouts. The trend continues today with projects like the huge Al-Fattah Al-Aleem Mosque (2019) near Cairo, which fuses contemporary engineering with classical Ottoman-style domes. In summary, modern Islamic architecture in Egypt is a conscious continuation of its heritage – preserving continuity in mosque design and urban skylines even as construction techniques evolve.

The following sections highlight key landmarks of Islamic architecture in Egypt and provide details on their significance, features, and visitor information.

Islamic Cairo: Key Landmarks in the Historic Capital

Historic Cairo (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) contains an unparalleled concentration of Islamic monuments (over 600 structures from the 7th to 20th centuries). The area known as Islamic Cairo includes the old walled city and nearby districts full of mosques, madrasas, fortifications, and bazaars. A walk down Al-Mu’izz li-Din Allah Street reveals medieval Cairo’s splendor – from the Fatimid-era Al-Aqmar Mosque to the gilded Mamluk complexes of Qalawun and Barquq Al Azhar Mosque History Al Azhar Mosque Cairo Egypt

Three landmarks stand out for visitors:

The Citadel of Saladin (Cairo Citadel): Founded by Salah ad-Din in 1176 AD as a hilltop fortress (Cairo Citadel – Discover Egypt’s Monuments – Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities the Citadel served as Egypt’s seat of power for 700 years – from the Ayyubid and Mamluk sultans through the Ottoman governors and even Napoleon’s occupation. Its imposing stone towers and walls still overlook the city. Within the Citadel are several monuments: Mosque of Muhammad Ali: The iconic 19th-century Ottoman mosque with its large central dome and twin minarets dominates the Citadel’s courtyard Cairo Citadel – Discover Egypt’s Monuments – Ministry of Tourism and Its interior is clad in alabaster (hence “Alabaster Mosque”) and features hanging globe lamps and Ottoman-style green and gold ornamentation. Non-Muslim visitors can enter outside prayer times; modest dress is required.

Al-Nasir Muhammad Mosque: A Mamluk-era mosque (1318–1335) notable for its green-glazed domes and well-preserved polychrome mihrab. This was the royal mosque of the Mamluk sultans.

Military and Police Museums: Housed in former palace buildings, these museums (including the 19th-century Al-Gawhara Palace exhibit weapons, uniforms, and historic artifacts, adding context to the Citadel’s military past.

Visitor Info: The Citadel is open daily from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM Cairo Citadel – Discover Egypt’s Monuments – Ministry of Tourism and Egypt’s

Cairo: Mosques and Citadels in the Capital

Cairo Citadel: One of Cairo’s most iconic Islamic monuments, the Citadel sits on a hill overlooking the city. Built by Saladin in the 12th century to fortify against Crusaders, it later became the seat of Egypt’s rulers for centuries. The complex includes multiple mosques, museums, and panoramic viewpoints. Notable sites within the Citadel include the Mosque of Muhammad Ali (the Ottoman-style “Alabaster Mosque”), the Al-Nasir Muhammad Mosque (Mamluk-era), and the Gawhara Palace Museum.

Visitor Info: Open daily 8:00 AM–5:00 PM (earlier closure during Ramadan and special holidays possible). Admission for foreigners is EGP 550 (~$18) for adults and EGP 275 for students. Egyptians/Arabs pay EGP 60. One ticket includes all sites inside. Tickets are sold at the main gate under the round keep known as Burg al-Haddad. Guided tours are available at the entrance or as part of a group tour. Plan 2–3 hours. Wear comfortable shoes – the site is on a slope, and some areas involve stairs. The terraces offer a sweeping view of Cairo’s skyline and minarets – perfect for photos on a clear day.

Al-Azhar Mosque: In the heart of Islamic Cairo, this mosque is both a spiritual beacon and home to the second-oldest continuously operating university in the world. Commissioned in 972 AD by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Mu’izz, it features architecture from many periods – Fatimid, Mamluk, Ottoman. Highlights include the Gate of the Barbers, minaret of Aqbugha, and the unique twin-finial minaret of Sultan Al-Ghuri. Inside is a large courtyard and a prayer hall supported by ancient columns.

Visitor Info: Open roughly 9:00 AM–5:00 PM daily (closed during prayer times). Entry is free. Dress modestly (long pants or skirts; women should cover hair with a scarf). Shoes must be removed before entering. A local guide is recommended to uncover the architectural and historical depth. The site is mostly accessible, with some uneven flooring. It’s conveniently located near Khan el-Khalili Bazaar – ideal for a combined half-day visit.

Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hassan: A masterpiece of Mamluk architecture near the Citadel. Built between 1356–1363, it includes a mosque, madrasa, and mausoleum. Known for its immense scale and unified design, visitors can admire the marble mihrab, wooden minbar, soaring iwans, and massive dome. The acoustics in the courtyard are especially impressive.

Visitor Info: Open daily, 9:00 AM–5:00 PM. Entry fee is ~EGP 80 (foreigners), EGP 40 (students). Modest dress required; shoes off inside. Guides are highly recommended for context. Allocate 45 minutes to 1 hour. Some steps at the entrance, but the interior is mostly accessible. Adjacent is the Al-Rifa’i Mosque, home to royal tombs and modern architecture that contrasts Sultan Hassan’s medieval grandeur.

Other Notable Sites:

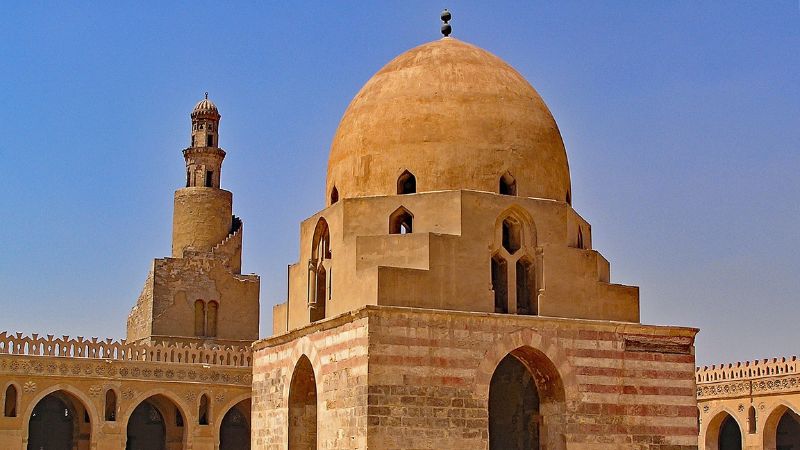

Ibn Tulun Mosque (879 AD): Cairo’s oldest surviving mosque in original form, with a vast courtyard and spiral minaret.

Museum of Islamic Art: Located in Bab Al-Khalq, featuring exquisite artifacts from various Islamic dynasties.

Khan el-Khalili and Souk al-Khayamiyya: Bustling markets with historic caravanserai and sabil buildings.

Egyptian Museum, Saladin Citadel & Bazaar Day Tour

Alexandria: Coastal Forts and Mosques

Citadel of Qaitbay: Built in the 15th century by Sultan Al-Ashraf Qaitbay on the ruins of the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria. It’s a classic sea fort with thick stone walls and towers offering panoramic views of the Mediterranean. Inside are chambers, staircases, and ramparts once used by Mamluk soldiers.

Visitor Info: Open daily, 9:00 AM–4:00 PM. Entry is EGP 200 (~$6) for foreigners, EGP 60 for Egyptians. Expect stairs and dim areas – bring a flashlight. Guided tours are recommended. Not all parts are accessible. Bring sunscreen for outdoor sections.

Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi Mosque: Alexandria’s largest mosque, redesigned in the 20th century in Moorish style. Dedicated to a 13th-century Sufi saint, it features beautiful domes, a towering minaret, stained glass, and colorful marble interiors.

Visitor Info: Open outside of prayer times (generally 9:00 AM–noon or mid-afternoon). No fee. Modest dress required; shoes off at the door. Accessible side entrances available. Guides not formal, but caretakers often provide info.

Other Islamic Landmarks:

Mosque of Nabi Daniel: Ottoman-style mosque with green dome; linked to legends about Alexander the Great.

Terbana Mosque: Small Ottoman mosque in Anfoushi district with unique wooden features.

Rosetta (Rashid): East of Alexandria, full of preserved Ottoman-era homes like Amasyali House, and its own Qaitbay Fort.

Luxor and Upper Egypt: Mosques amid Ancient Temples

Abu al-Haggag Mosque: A unique mosque built inside the Luxor Temple ruins. It honors a local Sufi saint and rests atop ancient pharaonic columns – a fusion of Islamic and ancient Egyptian architecture.

Visitor Info: Part of the Luxor Temple complex (open ~6 AM–9 PM, ticket ~EGP 160). Access into the mosque is limited, but it’s visible from below. Fridays are busy due to prayers. If visiting during the Moulid of Abu al-Haggag, expect a lively local festival.

Fatimid Cemetery (Aswan): A rarely visited necropolis with hundreds of 9th–12th-century domed tombs made from mudbrick. Early Islamic funerary architecture, peaceful desert atmosphere, and great photo ops.

Visitor Info: Free and open during daylight. No services or signage – bring water and wear sturdy shoes. A local guide is helpful for interpretation. Combine with a visit to the Nubian Museum.

Aga Khan Mausoleum: A modern 20th-century Fatimid-style tomb for Aga Khan III. It stands elegantly on a cliff across from Aswan. Though the interior is closed, the view from the Nile is stunning.

Practical Tips for Travelers

Best Time to Visit: Sites are open year-round. Avoid midday heat in summer. During Ramadan, visiting hours may change and prayer services increase, so plan accordingly.

Tours: Guided walking tours are popular in Islamic Cairo and recommended for deep insights. In Alexandria and Luxor, local guides can enrich Islamic site visits when paired with other monuments.

Etiquette: Dress conservatively. Women should carry a scarf; men should wear long pants. Remove shoes in mosques. Be respectful of worshippers, especially during prayers. Avoid flash photography.

Accessibility: Varies by site. Some mosques are largely flat and accessible; others (like forts or older mosques) have steps and uneven terrain. Tour operators can assist with accessible routes.

Tickets and Passes: Carry student ID if applicable. The Cairo Pass offers bundled entry to many monuments – check in advance which Islamic sites it covers.

Enhance Your Experience: Sit in mosque courtyards, stroll historic souks, or attend a nighttime event like a Sufi show on Al-Mu’izz Street. These moments bring Egypt’s living Islamic culture to life.