No other nation in the world says ‘Welcome’ as often as the Egyptians, and every time, they mean it. While the ancient civilization of Egypt continues to amaze, contemporary Egyptians are equally remarkable.

El-Ashmunein

El-Ashmunein: A Journey Through Time in Al Minya

Nestled on the western bank of the Nile, northwest of Malawi, lies El-Ashmunein, a site resonant with the echoes of ancient Egypt. Once known as Khmunw in Pharaonic times, this town was a bustling cult center dedicated to Thoth, the god of wisdom, healing, and writing, during the Old Kingdom era.

The Evolution of a Sacred City

In the Graeco-Roman period, El-Ashmunein, then known as Hermopolis Magna, gained prominence as the capital of the 15th Upper Egyptian nome. The city was a melting pot of cultures, where the Greek god Hermes was revered alongside the Egyptian Thoth. This fusion is epitomized by the site’s iconic colossal baboon statues, towering symbols of the god Thoth.

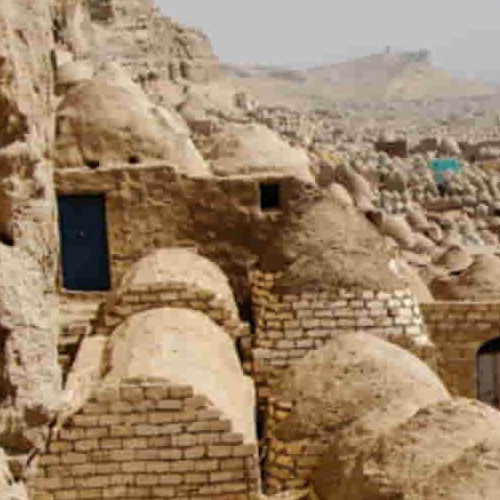

Khmun, meaning ‘town of eight,’ was named after the Ogdoad – a group of eight ancient deities embodying chaos before the emergence of the primeval mound. Sadly, the city’s earliest structures have not survived the sands of time, leaving only mounds of mudbrick ruins and remnants of stone temples, including the once grand Temple of Thoth.

Discoveries Beneath the Sands

In the 1930s, a German expedition unearthed the pylon of a temple constructed by Rameses II, revealing over a thousand talatat blocks from el-Amarna’s Aten temples. Later, from 1980 to 1990, the British Museum’s Jeffrey Spencer and Donald Bailey led excavations that uncovered New Kingdom temples, artifacts, and a prominent street known as the ‘Dromos of Hermes’.

The Open-Air Museum: A Portal to the Past

Visitors to El-Ashmunein are greeted by an open-air museum at the old archaeological mission house. Here, you’ll find statues and stelae, including two reconstructed baboon statues representing Thoth, standing over 4.5 meters high, dating back to the reign of Amenhotep III.

The site’s main attraction is the great Temple of Thoth, enduring despite extensive stone quarrying over the centuries. The remnants of Nectanebo I’s reconstruction and Rameses II’s and Horemheb’s pylons mark the temple’s historical significance.

The Temple’s Architectural Marvels

The Temple of Thoth boasts structures from Necatnebo I’s era, including a massive mudbrick wall. Alexander the Great’s portico addition, though now in ruins, was once a spectacle of limestone columns and vibrant decoration.

Nearby lies the Amun sanctuary, constructed by Rameses II, showcasing Merenptah and Seti II’s relief works. The area also houses the remnants of a Middle Kingdom gateway, believed to be the original entrance to the Temple of Thoth.

Beyond the Temples

El-Ashmunein’s history is further revealed through a Roman Agora and a restored Coptic basilica, showcasing a blend of Ptolemaic and Greek architectural styles. These structures, along with inscriptions, shed light on the social dynamics and religious practices of the time.

The townsite of Hermopolis, excavated by the British Museum team, offers a glimpse into the lives of its wealthier inhabitants, with well-preserved mudbrick houses and a processional street adorned with historical artifacts.

A Cemetery Steeped in History

The oldest discovery at El-Ashmunein is a Middle Kingdom cemetery, excavated in the 1980s. Surrounded by a vast mudbrick wall, the tombs reveal a rich tradition of burial practices, with pottery offerings typical of the era.

In summary, El-Ashmunein in Al Minya is not just an archaeological site; it’s a portal to ancient civilizations. As you wander through the ruins and museums, the whispers of the past come alive, offering an immersive experience into Egypt’s rich and storied history.

Created On March 18, 2020

Updated On Aug , 2024